Just released!

Our latest CD

Purchase Tickets Online securely with

buy season subscription

tickets and save

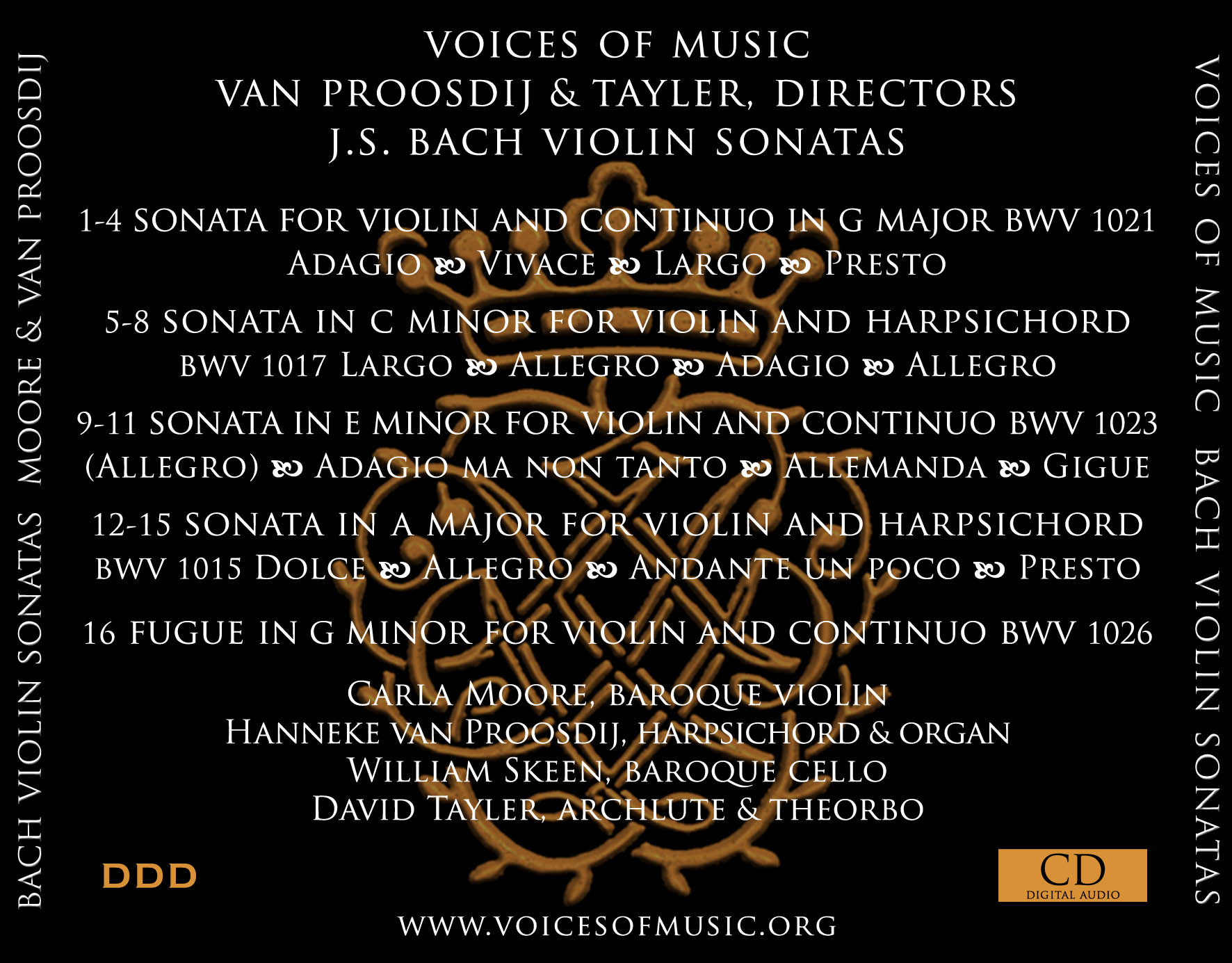

J.S. Bach Violin Sonatas--available at concerts now and online through our dedicated CD server

In comparison to the rich legacy of instrumental and vocal music preserved in his cantatas, relatively little chamber music of J.S. Bach survives. Surely there must have been more, as historical accounts suggest a lively musical scene for instrumental music not only from Bach’s Cöthen period but also but also, as Christoph Wolff suggests in his 1985 article on Bach’s chamber music, from his tenure at Leipzig. The works which do survive are compositions of extraordinary refinement, and the sonatas for violin, with both continuo and obbligato parts for keyboard, are among the best of Bach’s chamber music. Although it is impossible to say for certain if Bach created this new genre, he was certainly the first to write a significant number of complex pieces using this new technique. The quality of these pieces and their position in history is reinforced by a brief note penned many years after their composition by Bach’s son, Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach: “The six harpsichord trios are among my dear father’s best works. Even after more than fifty years, they still sound excellent, and are delightful." A comparison to the Brandenburg concertos may be drawn not only in the way the sonatas are collected but also in the tightly-knit compositional style which emphasizes all of the varied skills of the baroque musician, from cantabile playing to episodes of ferocious complexity and virtuosity. The manuscript sources present a number of different titles for these works, but a common thread may be seen in the following: Sei Suonate à Cembalo certato è Violino solo (“certato” here means that the keyboard part is written out in full). The title emphasis the partnership of the harpsichord and violin (with the harpsichord here receiving top billing).The collection of six pieces was numerically significant to Bach, as musicologist John Butt has noted: Bach liked groups of six, and, like the six Brandenburgs, the collection was probably drawn from several different sources. |

|

||

A number of writers have suggested that owing to the primary position of the word “cembalo” and the word “certato” in the title, these pieces are really harpsichord sonatas with violin accompaniment. A survey of all the titles in all of the sources reveals that all of the titles are different, and that the pieces are often referred to only as “violin solo” or “violin sonata.” However, the word “certato” in the title does importantly signify a new and exciting development in the composition of instrumental sonatas: a method in which the keyboard player is provided with an intricate, written out part which essentially creates the sound of a trio sonata--the right hand of the keyboard instrument often sounds a melody in the manner of a second solo instrument. One of the true delights of preparing this program, and in reading about the history of these pieces, was working with the seldom-performed Fugue in G Minor for Violin and Continuo BWV 1026. An unusual piece in many respects, the Fugue combines a number of contrapuntal devices over an imitative and harmonic framework, and, needless to say, requires every ounce of technique from the soloist. Extended episodes of two part writing are leavened with triple stops and an extended pedal point alternating between the D strings of both the violin and the cello. Of the Fugue, violinist Carla Moore writes: “What a wonderful surprise was in store when I opened the score of Bach’s complete sonatas for violin and harpsichord, and discovered the G Minor Fugue. I had never come across this work before—it is not in any edition of the sonatas I have seen, and is not part of the standard Bach sonata repertory. It reminded me of the excitement and thrill of discovery I experienced in college when I began performing music by composers not taught in the modern violin curriculum—Biber, Castello and Couperin—and how it changed forever the way I think about music. What a wonderful treat it has been to learn this suspenseful, high-energy piece.” The violin sonatas present a small number of musicological puzzles. Some of these, such as the position and number of the slurs and trills are simply worked out according to our best musical judgment. A particularly thorny issue that comes up time and again in baroque performance is that of places in the music in which the parts are written in different meters: |

|

|

|

|

|||

Hanneke van Proosdij performs regularly as soloist and continuo specialist and is principal early keyboard player with Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra, Festspiel Orchester Goettingen and Voices of Music. Hanneke received her U.M. (solo performance degree) and D.M. from the Royal Conservatory of the Hague in the Netherlands, where she studied recorder, harpsichord and composition. She has appeared regularly with Hesperion XX, Concerto Palatino, Magnificat, American Bach Soloists, the Dallas Symphony, Concerto Koln, Chanticleer, Gewandhaus Orchester and the Arcadian Academy. Together with David Tayler, Hanneke cofounded and codirects Voices of Music. Hanneke is a cofounder of the Junior Recorder Society in the East Bay and directs, together with Rotem Gilbert, the SFEMS Recorder Workshop. She has recorded over fifty discs for Magnatune, BIS, Koch, Musica Omnia, Carus, AVIE and Delos. Hanneke teaches recorder at UC Berkeley and has been guest professor at Stanford, Oberlin, Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, the University of Wisconsin and the University of Vermont. Hanneke enjoys reading books and hiking.

|

|||